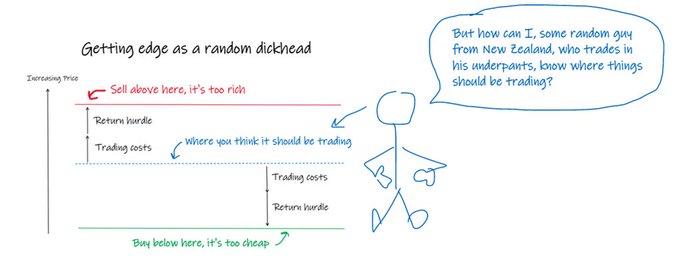

how to make money as a random dickhead

trading requires us to buy things cheaper than they should be / sell things richer than they should be.

but how could i, some random guy from new zealand who trades in his underpants, know what things should be worth?

the short answer is i don’t.

i don’t have a clue.

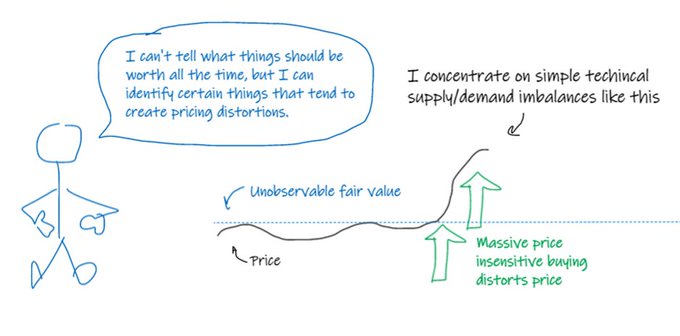

thankfully, i don’t need to be able to know what things should be worth all the time.

it’s enough to be able to find when they’re likely to mispriced, on average.

i concentrate on simple technical supply/demand imbalances.

mostly, i look to get paid to do useful things in uncompetitive places: “doing useful things that suck’

lemme explain what i mean.

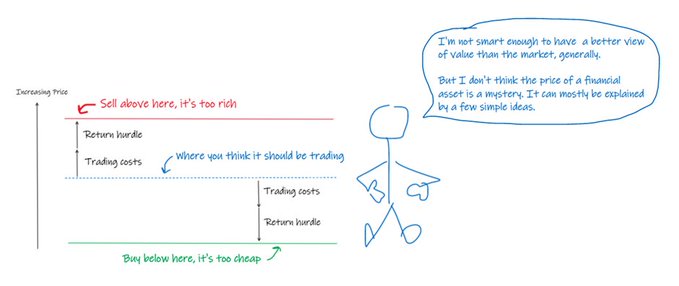

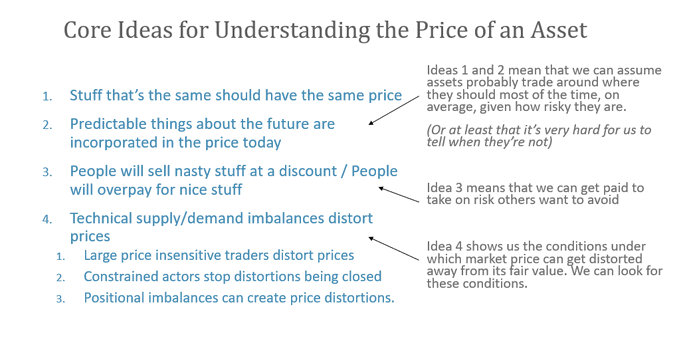

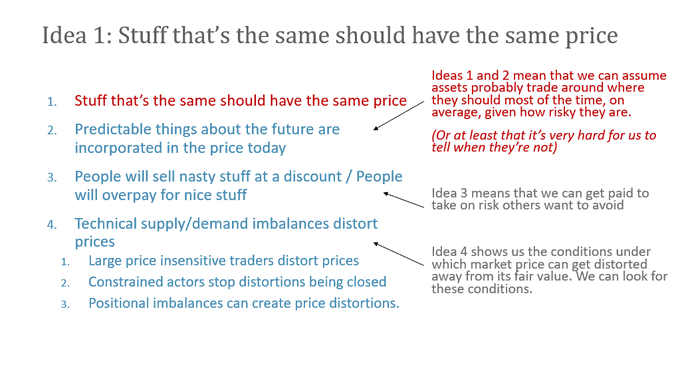

i don’t think the price of a financial asset is a mystery.

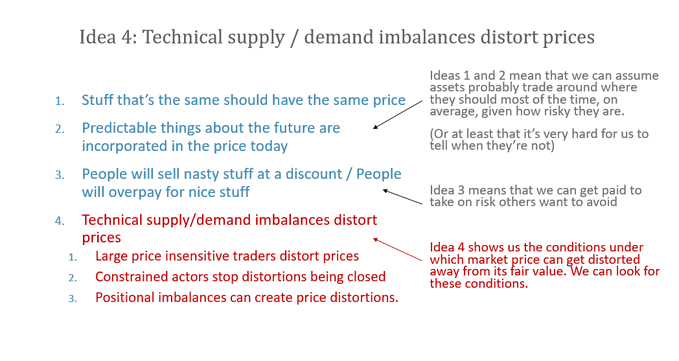

i think it can mostly be explained by the following ideas.

- stuff that's the same should have the same price

- predictable things about the future are incorporated in the price of the thing today

- ppl will sell you nasty stuff at a discount

- people who don't care about price distort prices

- forced or constrained people distort prices

- positional imbalances can create price distortions.

if you’re in a hurry, the main point of this thread is that:

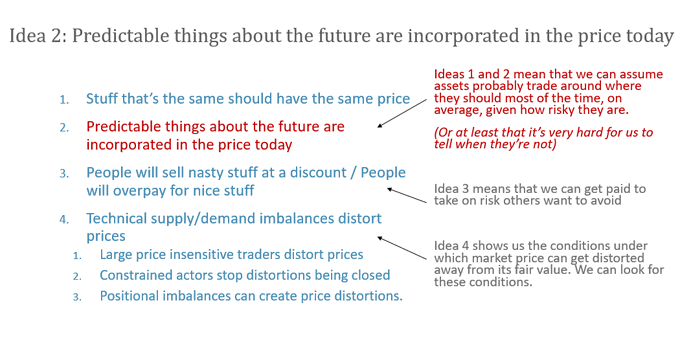

ideas 1, 2 mean that you can assume that risk assets are fairly priced most of the time.

(or, at least, they are on average and ppl like me can’t really tell when they’re not.)

idea 3 means that risk assets tend to trade below where the value implied by their expected returns, because they are risky.

we call this a risk premium. and it is why you expect to make money over the long run long stock indexes, bonds and other diversified risky assets.

by the time we get to ideas 4 and 5, we can simplify to “assets probably trade around where they should be most of the time, given how risky they are”

this is good news because it means we can stop worrying about modelling this. The market probably got it right enough, at least on average.

and if we're fishing for inefficiencies, as a random dickhead, we can focus on idea 4: technical supply/demand imbalances created by forced or constrained actors are likely to create pricing distortions.

let's go through the full list tho, and discuss how edge can be extracted.

idea 1 - stuff that's the same should have the same price

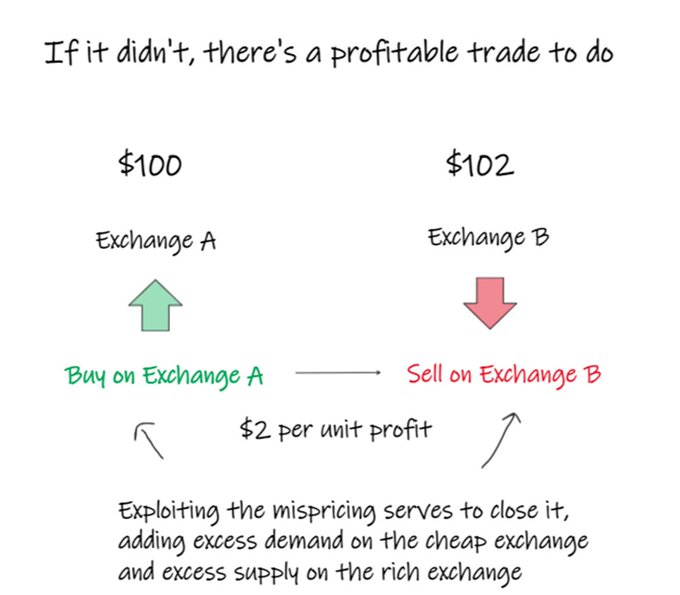

trivial example: if shares in the same asset trade on two different exchanges, they should have the same price on each of them.

if they didn't you could:

- buy it where it's cheap

- sell it where it's rich

- profit

...which would be nice.

but things you think are nice are attractive to others too.

so, these kinds of things are super competitive.

they don't sit around long.

opportunities like this don't sit around long and are mostly out of reach to people like me, trading in my underpants from a bunch of excel and bad code and sticky tape and espresso.

but similar, riskier, ideas are available.

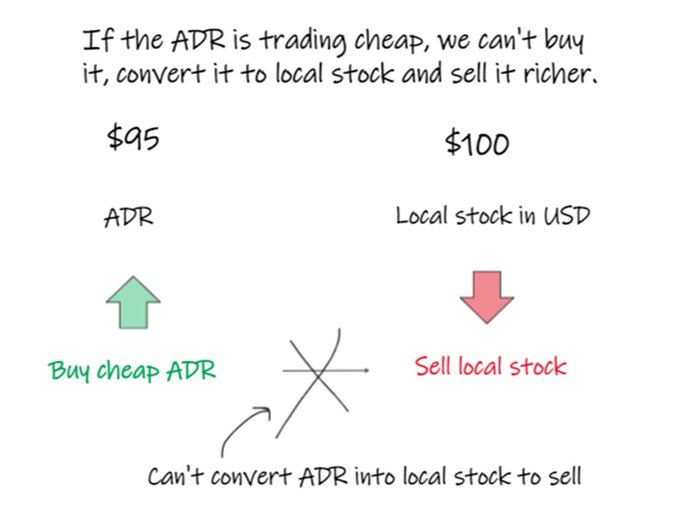

for example, an american depository receipt (adr) is a certificate representing shares in a foreign company that’s listed on a non-us exchange.

they trade like stocks. and they're why you can trade baba, sony, nio etc on us exchanges.

it’s pretty obvious what the value of the adr should be in ideal, frictionless circumstances (the usd value of the equivalent local shares.)

but, if the adr is trading cheap, we can’t buy the adr cheap and convert it to foreign shares to sell.

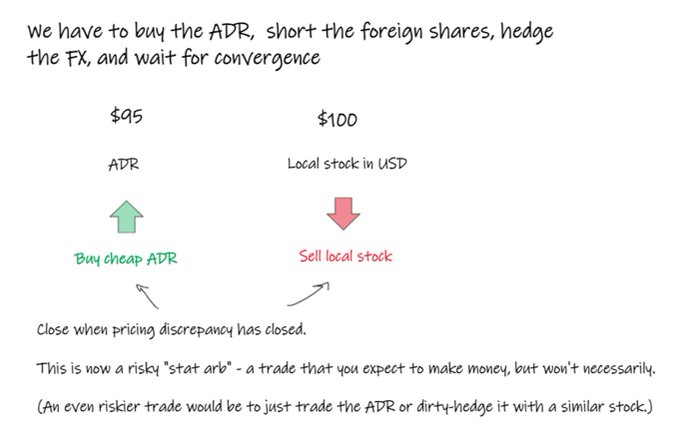

instead we have to do a riskier trade where we long the adr, short the foreign shares, hedge the FX if we have to.

(or, if you’re a degenerate like me, just trade the adr if you think it’s mispriced, and eat the risk or "dirty-hedge" it with a similar stock. and, in the real world, liquidity and funding issues make this trade more complicated than presented here.)

more complicated ideas are also available.

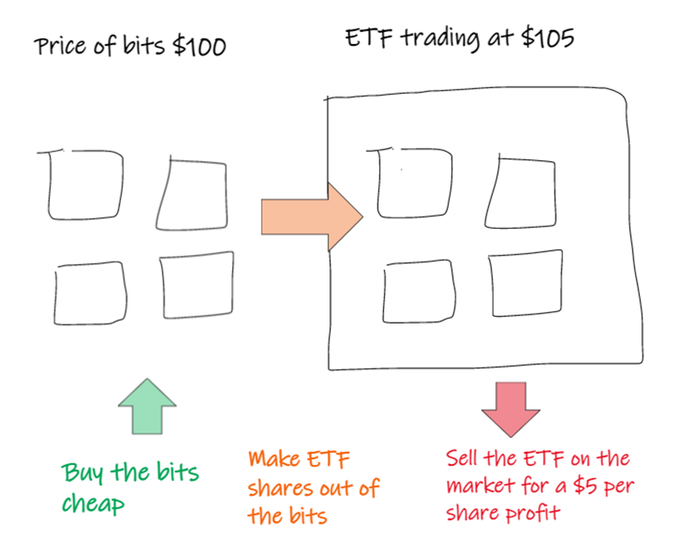

if you can recreate the payoffs of one thing with another thing, then those things should have the same price.

if they don’t, someone will trade the thing and the replicating basket of things for profit.

and the excess supply/demand generated by this trading will start to close the opportunity.

you can think of it as the person doing the trade getting paid to push the market back towards equilibrium.

examples include:

- making a call option out of a put and a stock

- making an etf out of the assets it holds

- recreating the payoff of an equity index futures position from the share basket, less dividends, plus interest

- etc.

these opportunities are extremely attractive.

they are obvious dislocations and very high risk-reward trades if you can be the person that closes the mispricing.

doing this stuff is a business.

not generally something some dickhead like me can exploit.

except sometimes i actually can.

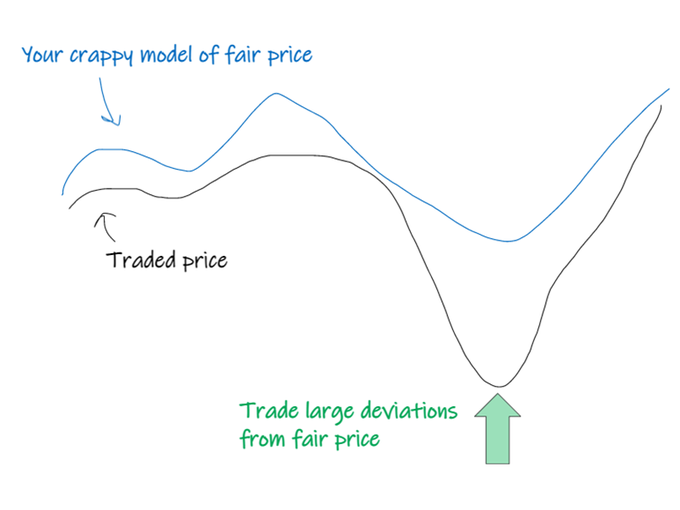

for example, sometimes a brand-new stupid thing launches.

there isn’t any data on it.

nobody can see how it traded in the past, cos it hasn't traded.

but often you can build a crude model for where it should trade relative to other stuff.

and, for a short while, you can often get away with trading large deviations from your (knowingly) crappy model.

and you'll carry oun until the environment gets more competitive. then you take your ball and go look for other sloppy opportunities.

a recent example is the ftx move contract.

this was basically a straddle, struck at a non-standard price, plus some other quirks.

so you have could built a crappy model of where it should trade, based on tradeable options prices and/or views on future volatility.

and it turned out that a crappy model was all you really needed.

because whoever was quoting it (alameda or someone they outsourced to, presumably) did a lousy job of it to start with.

until they tightened that up, you could sit and wait and pick off obviously attractive quotes.

obvious and high-risk reward trades like this can sometimes be found in new and highly fragmented markets.

crypto and defi recently gave me an opportunity to be involved in obvious trades like this.

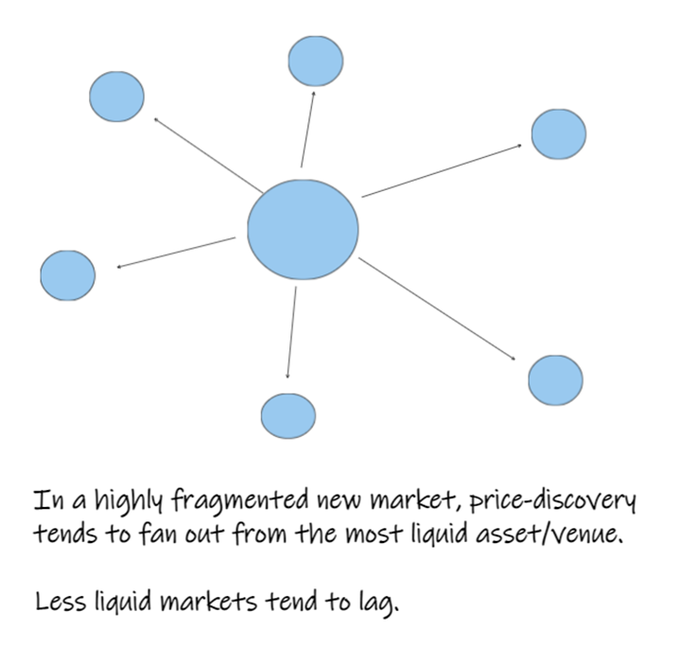

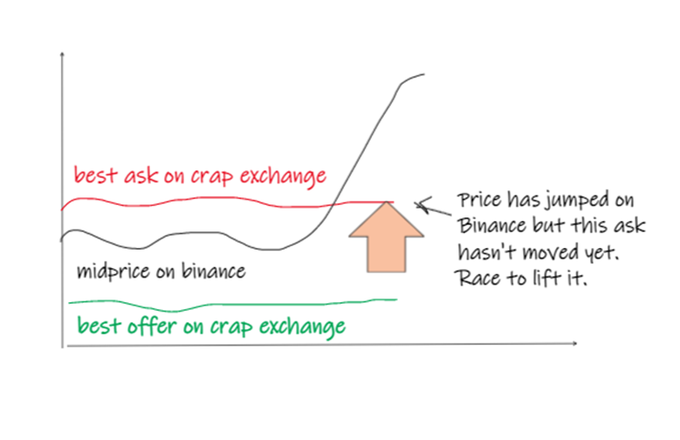

crypto is very fragmented. the same (or similar) things trade in lots of places.

and "price discovery" doesn't typically happen everywhere at once.

it tends to happen in the most liquid asset/venue and then fan out, on a lag.

this meant that simple trades were available that looked like:

- “if the price on Binance jumps, race to buy in other places”

- "if the e-mini jumps, spam buy orders on-chain"

i mostly did this on-chain on solana, where massive execution variance further advantaged opportinistic sniping.

this kind of obvious high risk-reward fun and games doesn’t last long for dickheads like me, cos they quickly attract other firms who are technically far more capable.

so, you can’t depend on trades like these. they don’t come along all the time and they don’t stay long.

but, when they arrive, get your blood funnel in ‘em, and suck as much money out as you can.

(my biggest trading regrets are always not sucking enough money out when the going is really good.)

so, trades around Idea 1 (replication trades) are mostly out of reach. but they're sometimes available if you pay attention.

idea 2 - predictable things about the future are incorporated in the price of a thing today

we’ll get through this one quick.

we can look at what an asset is, model the fundamentals, forecast into the future, and build a securities pricing model to work out where an asset should be trading now, based on “rational expectations” about the future.

well, other people can do that. i can’t.

there are a ton of very smart, well-informed analysts and investors out there, talking to people, rocking excel dca models and betting on their views.

the combined effect of this means it's very hard for an individual to have a better view on value than the aggregate market.

and, even if you could do this in one security, it’s very hard to do it with the scale or breadth needed to trade in a persistently profitable way.

so, the idea of me getting edge like this goes straight in the “too hard basket”.

i assume that most things are probably fairly priced, given the risk, most of the time, on average.

or rather, i assume that i have no way of telling when they’re not by analyzing fundamentals.

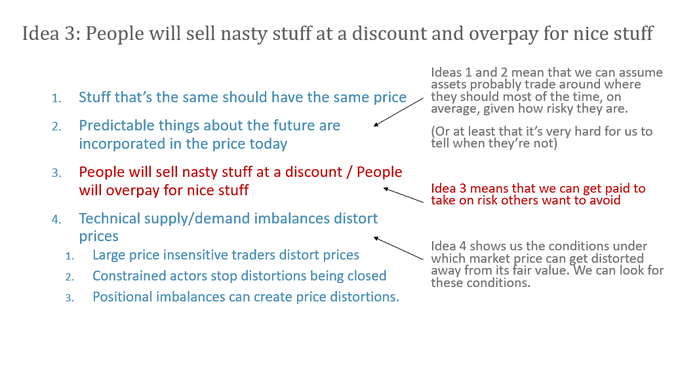

idea 3 is next.

it's about the “given the risk” part...

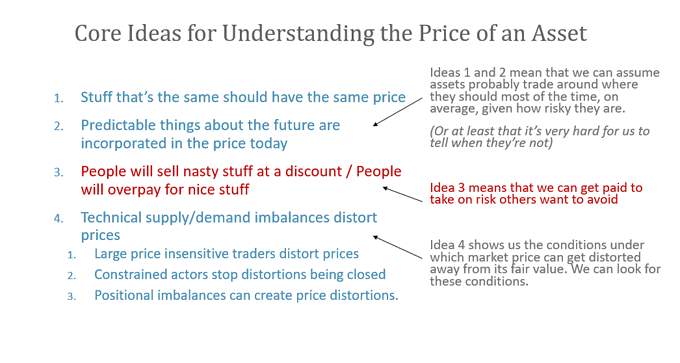

idea 3 - people will sell you nasty stuff at a discount

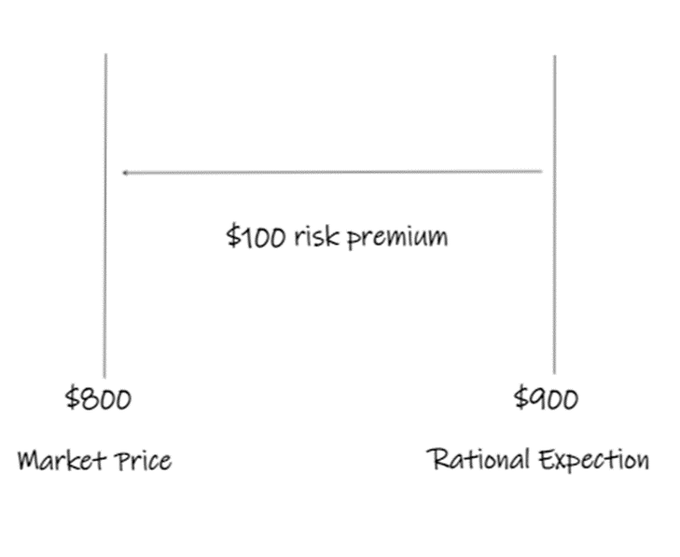

when those people with the excel models come up with a price of an asset based on “rational expectations”, they’re going to come up with a number higher than the market price of the thing.

why?

cos people dislike risk and uncertainty.

consider a corporate bond in a company that is:

- 90% likely to repay

- 10% likely to not repay.

the rational fair price of the bond is 90% of its face value.

but, it’s risky, there’s 10% chance you’ll lose all your money.

nobody wants to make a risky bet like that, unless they think they’ll be rewarded for taking on that risk.

and sellers will be prepared to sell it for less than it’s expected “fair value” because it’s risky too.

so the bond might trade at 80% of its fair value.

the 10% discount between traded price and "rational expectations" represents a “risk premium” for those prepared to take on that risk.

this is the easiest and least competitive way to make money in financial markets.

get paid to take on risk that others are keen to avoid.

btw, this works the other way around too.*

things people like are usually too expensive:

- positive skew

- lottery-like assets with embedded leverage.

so, avoiding these things (or selling them if you can manage the risk) can be a good idea, too.

the wealth management industry is built around these idea.

if we can diversify across lots of risk assets, we can harness this risk premium.

practically, this means buying stock and bond index products, accepting the risk, and being patient.

other opportunities we might put in this “risk premia” basket include:

- long biased equity

- yield curve carry

- vix forward rolldown

- selling equity index volatility

- other forms of carrywhoring

- buying discounted close end funds

- weekend / business hour effects.

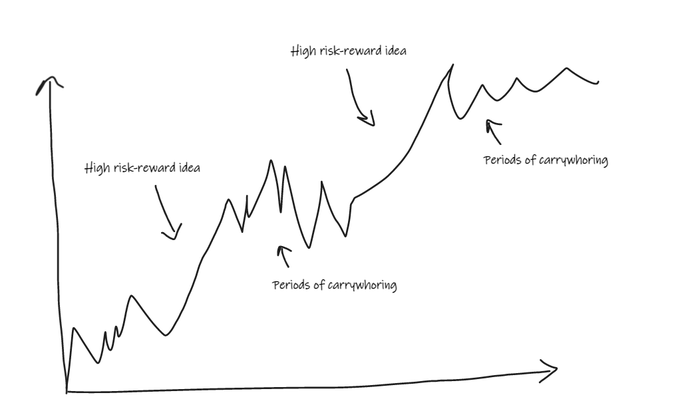

i usually camp out in these trades when i don’t have any higher risk-reward ideas i can implement.

as a result, my pnl stylistically tends to look like this.

short periods of high risk-reward profit broken up by noisy periods of carrywhoring.

(i am in carrywhoring phase at the moment)

ok phew.

we made it to idea 4. the thing i really wanted to discuss.

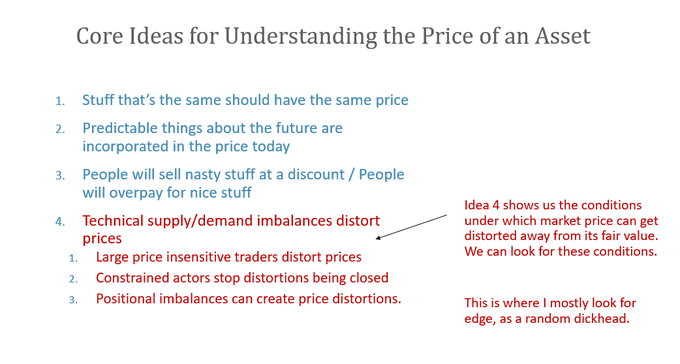

idea 4 - technical supply/demand imbalances distort prices

by the time we got to idea 3, we determined we can assume most things are probably fairly priced, given the risk, on average.

or, at least, I can’t tell when they’re not, based on fundamentals.

now, markets are basically supply / demand balancing machines.

- excess demand make price go up.

- excess supply make price go down.

most of the time, supply and demand is strongly dependent on perceived fair value.

- more people will want to buy if they think it's cheap.

- more people will want to sell if they think it’s rich.

but people will trade for all kinds of reasons that have nothing to do with price or value, too.

- maybe they're trading simply because they have other objectives?

- maybe they're trading cos they have to, even though they don't want to?

here are some ways we can take advantage of that.

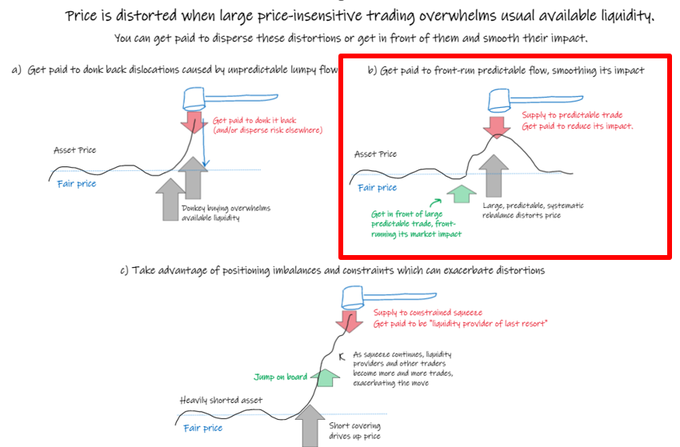

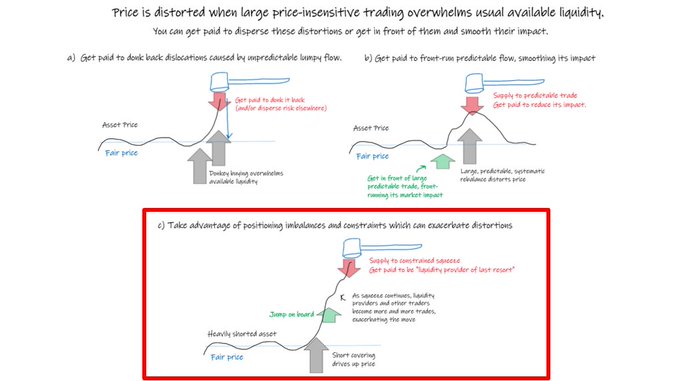

We can:

- get paid to donk back dislocations caused by unpredictable lumpy flow

- get paid to front-run predictable flow, smoothing its impact

- take advantage of positioning imbalances and constraints which can exacerbate distortions.

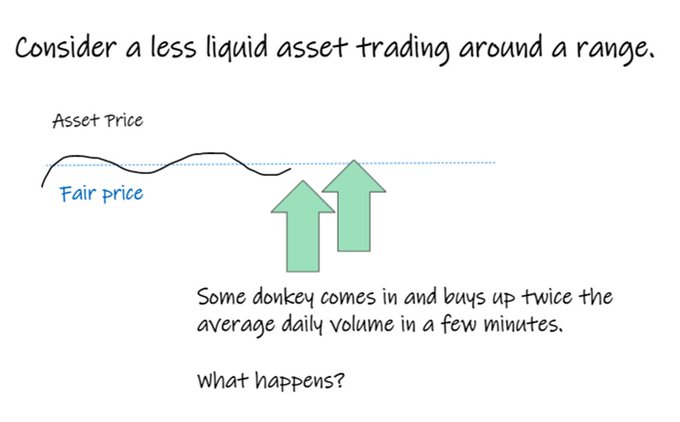

1. get paid to donk back distortions caused by unpredictable lumpy flow

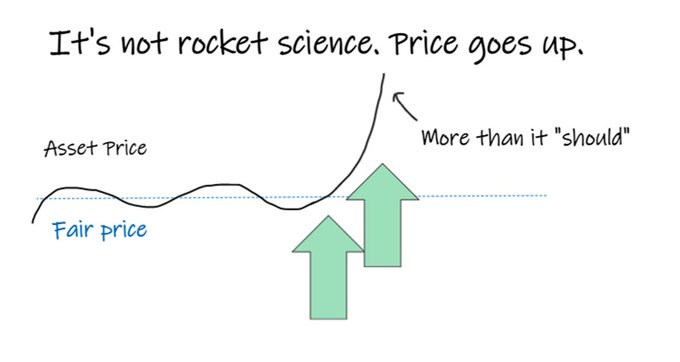

imagine a less liquid asset is happily trading around a range, and some big donkey comes along and buys twice the average daily volume in a few minutes.

what’s going to happen?

well, it ain’t rocket surgery.

price is going to go up. way more than it “should”.

large, price-insensitive trading creates pricing distortions when it overwhelms the usual available liquidity.

this is usually caused by large traders that don’t care about price, people who have to trade (rather than want to), or people with misaligned objectives.

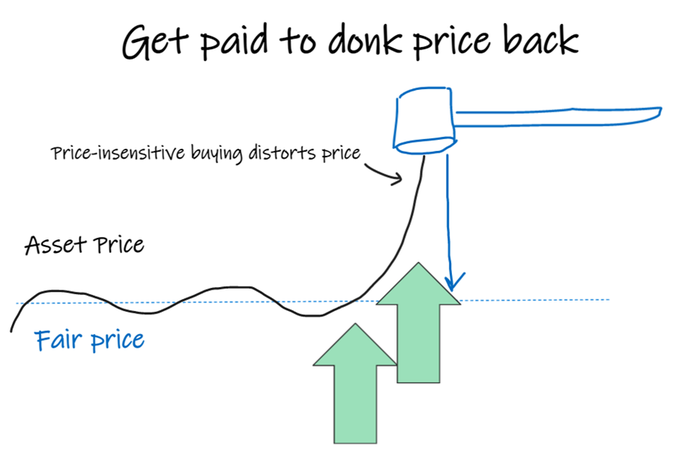

if you can identify this, you can get paid to donk it back.

but you don’t necessarily need to know exactly when price dislocations have occurred: just be in position for them, on average.

being right on average is enough.

this is typically done on a relative value basis.

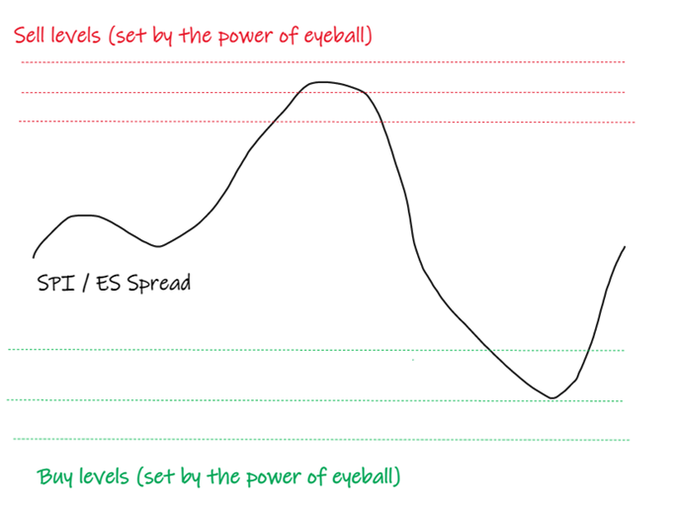

one of the first systematic trades I ever did was spreading equity index futures against each other.

for example, consider the spread between spi (s&p/asx 200 futures) and es (s&p e-mini futures).

i’d plot the intraday spread.

when the spread moved to intraday extremes it was likely this was caused by lumpy flow in spi, which was slightly more likely to revert than continue.

i used the level of the spread as a very crude proxy for lumpy flow in spi (or maybe even es) distorting relative prices.

the trade was simple. i’d eyeball levels to buy and sell the spread after the US market cash close.

there’s nothing precise about this.

i was wrong a lot.

but i was generally in position, on average, to take advantage of lumpy flow distorting prices.

sitting in roughly the right place, on average, to push back dislocations.

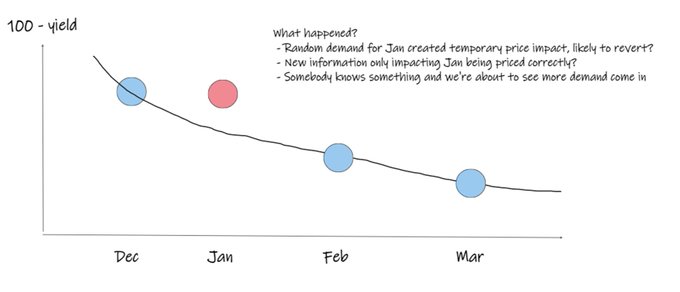

i also did similar trades in STIR futures in a more discretionary manner.

pricing relationships between contracts are easier to quantify than between different equity index futures.

but the idea is basically the same.

get paid to donk back things that are likely, on average, to be dislocations caused by lumpy flow.

most of statistical arbitrage is this idea.

you’re fading relative dislocations and trying to offset the risk as best you can.

it’s a crude idea. a blunt approach.

you’re just trying to sit in roughly the right place at the right time, on average, to donk pricing dislocations back and disperse the risk elsewhere.

2. get paid to front-run predictable flow, smoothing its impact

more interesting trades are available when you can predict when price-insensitive trading is likely to occur.

if you know some price-insensitive trading is likely to happen, you can get in front of it and then provide to it.

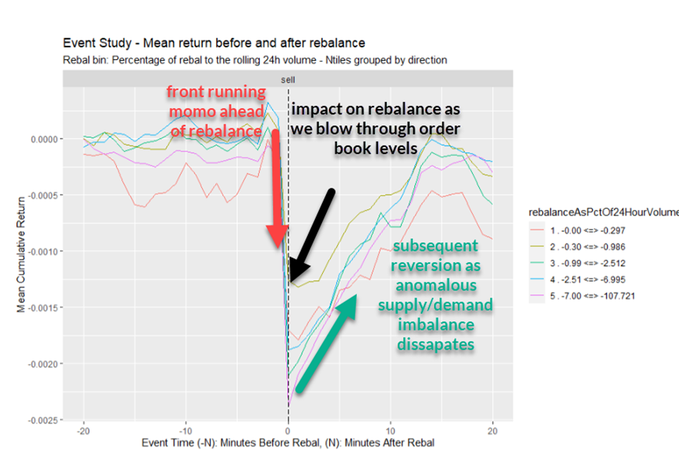

here’s an obvious example...

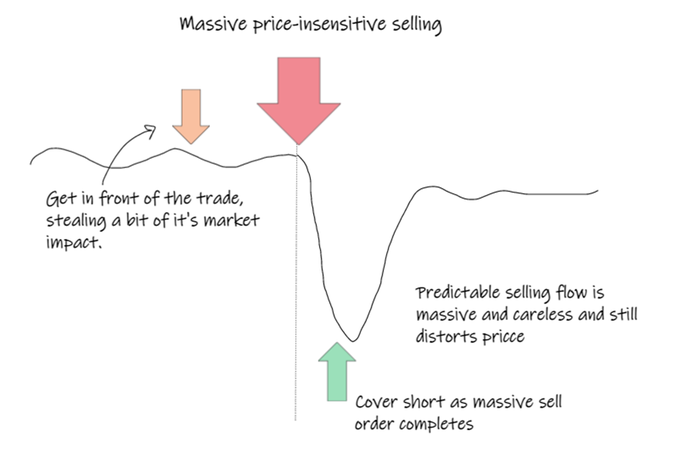

go back in time to before sbf stole your money.

you know that someone will come into the ethereum futures market on ftx a few minutes after midnight and sell $10mm of futures contracts regardless of the price it's trading at, in a couple of transactions, over a few seconds.

that’s at least 10x bigger than the normal trading volume that will occur in a minute.

what’s going to happen?

well… we don’t need to overthink it.

a ton of price-insensitive supply, if not fully absorbed, will make price go down.

then, when selling completes, we'd expect price to rebound back.

the trade didn't have any information associated with it – just someone who needed to get a large trade done.

so we'd look to get in front of it, selling ahead of the trade. then cover our short as the selling completes.

this actually happened on ftx every day.

it’s due to carelessly executed rebalancing trades from ftx leveraged tokens.

these were tokens that attempted to match a multiple of the returns of a crypto index

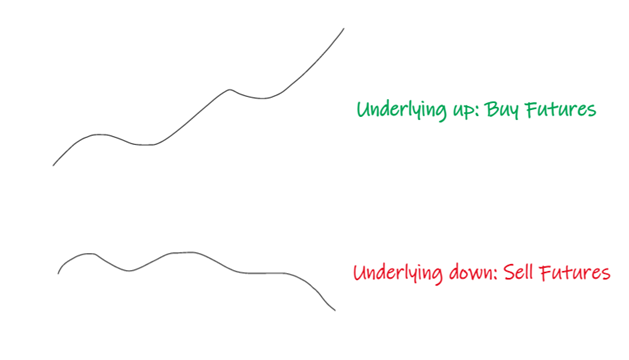

all you need to know is that:

if the market has gone up (down) today, the fund is buying (selling) futures on the exchange to maintain it’s leverage target

and it’s doing it mechanically, in a price-insensitive way.

and it had exactly the impact we thought it would.

and, given we knew exactly when it was happening we could position ourselves in advance to front-run it, and then provide to it.

your trading here is balancing out an imbalance, leading to a slightly more orderly market, and slightly less terrible execution for the fund.

you’re getting paid to smooth out predictable market impact.

rebalances, predictable de-leveraging, liquidations, tax harvesting, employee share vesting, dividend reinvestment programs can all be the cause of large predictable price-insensitive that can distort price.

you can get paid to front-run it and smooth out its impact.

but things aren’t usually as clear cut as this example…

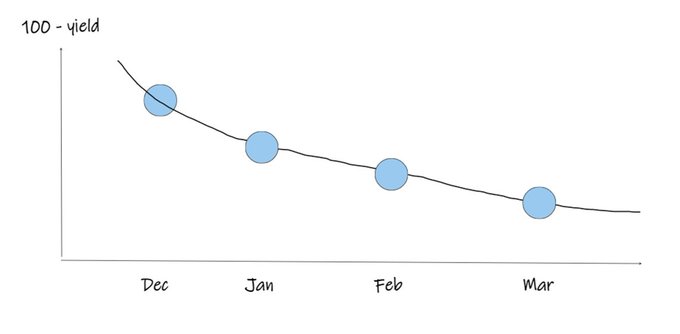

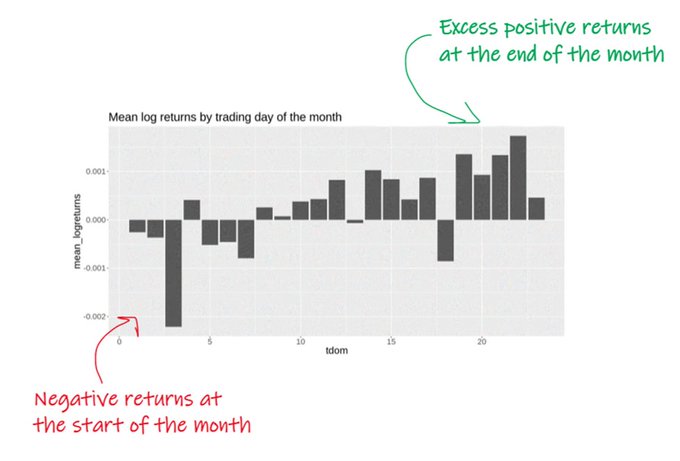

for example, we see day-of-the-month seasonality effects in treasury bonds.

if we plot the mean total log returns for holding a tlt (treasury bond etf) position by trading day of the month, it looks like this:

- negative returns start of month

- excess positive returns end of month

why?

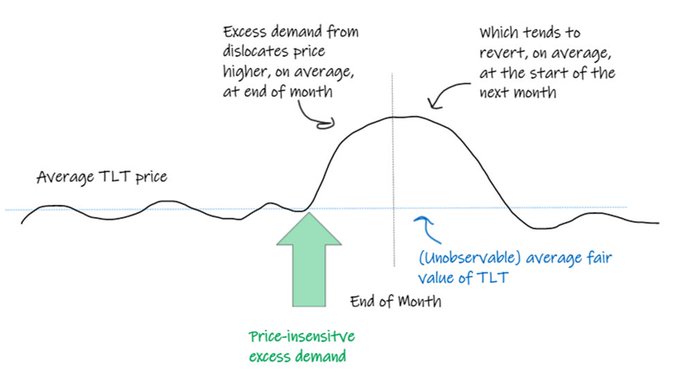

it suggests there’s price-insensitive excess demand towards the end of the month.

this would result in treasury bonds becoming too rich at month-end

which we’d expect to revert at the start of the next month.

this might be due to:

- fund managers window-dressing (rotating into more conservative assets for month-end disclosures)

- mechanical bond etf purchases around month-end to maintain fund target duration

we can never really know why but we have a lot of evidence and some plausible causality.

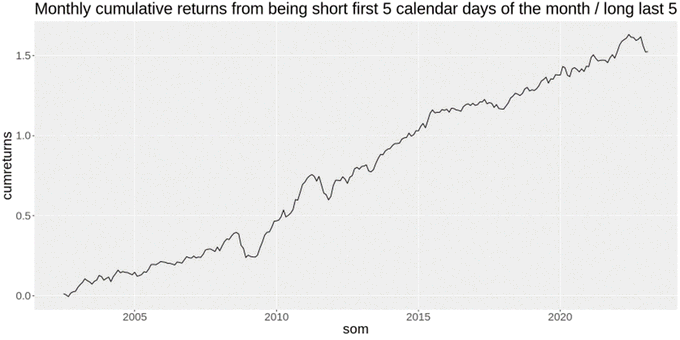

so you might exploit this idea with any simple strategy that is:

- short at the start of the month

- long at the end of the month

for example:

- buy tlt 5 days before end of the month

- reverse short on the last day of the month

- cover short 5 days into the month

the precise rules don’t matter. these effects are just blunt, noisy tendency, not something you can ever be precise about.

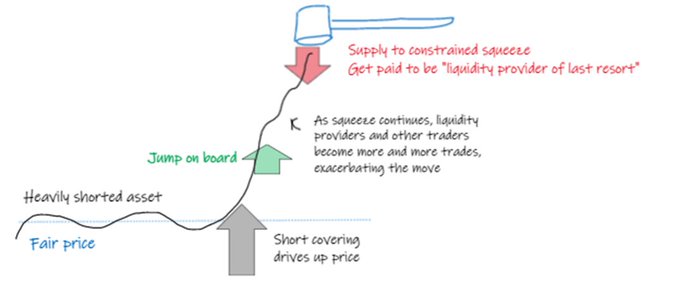

3. take advantage of positioning imbalances and constraints which can exacerbate distortions.

our final category is taking advantage of positioning imbalances and constraints:

market prices generally stay close to where they “should” be because, if they are not, other traders will step in and get paid to push them back.

sometimes the traders who would do this are heavily constrained, so they can’t.

this can happen in extreme market environments or short squeezes.

it's also the case with derivatives too.

for each derivative contract, there is a party who is long and a party who is short.

(this is not true of a stock or physical commodity.)

we can crudely divide the parties into two groups:

customers - move price, often in a “self-defeating” manner, crowd into similar positions, are slow to respond to information, on average.

dealers - usually passive, actively take advantage of distortions created by customers

if you marked out trade pnl for each side, you’d see dealers generally have the best of it.

you’d take the dealer side of trades if you could.

you can't usually. that's competitive.

but sometimes things get very lopsided, leading to under-reaction effects when exciting things happen in products like VIX future, as described here: https://twitter.com/therobotjames/status/1526679212882825216

summary

anyway... i have spoken too much.

the point is, if you are random d1ckhead like me, sometimes really juicy opportunities come along (idea 1) but we can't rely on that.

the best places to go looking for edge are:

- harvesting risk premia

- technical supply/demand imbalances

good luck in your trading, friends.

beep...boop.

a course i'm teaching with euan sinclair

oh, and if you made it this far, you'll like this course on option trading i'm teaching with euan sinclair. these ideas are discussed there as well as lots of examples of options trades.

you can find out about that here: https://twitter.com/therobotjames/status/1638312972421570560?s=20